What it's like to row across the Atlantic SOLO - I made it in 96 days!

With my family in Barbados after spending 96 days at sea.

Preparing for the Solo Atlantic Row

It had taken me one year to prepare for my transatlantic solo crossing and 96 gruelling days to complete it. I have experienced rough seas, sea sickness, multiple problems with my manual steering set-up, leaky hatches, problems with watermaker, etcetera, etcetera. Most importantly, I had to fight my inner demons of despair, self-pity and self-doubt, which were telling me to quit. Despite all that, I kept on rowing taking each day as a separate challenge and feeling like I was still standing at the end of it being hit over and over again by the force that was of such magnitude that it often felt like fighting it was absolutely pointless.

My favourite part of the day was when I took my life jacket off at the end of my 12-14-hour shift knowing that I gave it everything I had there and then. I often felt broken and defeated, but not at my core. I never stopped rowing, only when I had to go on para-anchor due to particularly rough conditions, which made it completely impossible to row. I did not have any maritime experience when I started off. It was my grit and a deep desire to keep standing up that saw me through.

I also experienced the immense beauty of the vast Ocean, a unique experience of being there in a small boat, completely alone, but feeling a presence of something bigger than me in every sense of the word. That profound experience has changed me in more ways than I realise as I am writing this. One thing I know for sure is that I cannot betray it and have to live up to it now.

The Journey Begins: Towing to Gran Canaria

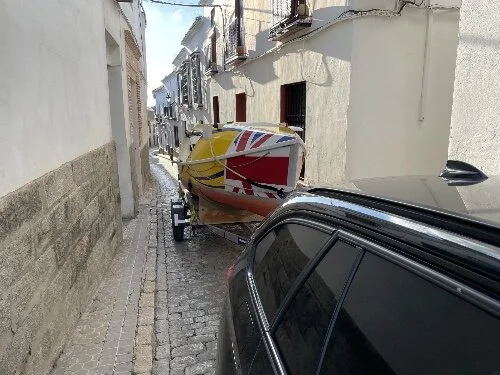

My adventure started on dry land. I decided to tow my boat to Gran Canaria, which involved two ferries and driving through the whole length of Spain in between. It was an uneventful and enjoyable journey, which took me 5 days in total and the biggest challenge towing the boat through crooked narrow streets of Spanish medieval towns in search of the hotel. I was really glad that I had taken some towing lessons and driven the boat on a few occasions back in the UK previously!

Departure Day: Setting Off on Boxing Day

I arrived at Marina Puerto Rico in Gran Canaria on December, the 15th. My mentor and coach Dave Bell was waiting there for me. The guy had torn his ACL (an important knee ligament) two weeks prior to my departure and was on crutches when I saw him. He also drove my car and trailer back to the UK (thankfully, an automatic!) a few days later after doing the final checks with me and making sure the all the onboard systems were working properly. It is a testament to the measure of the man and what he stands for, and I will never forget what he has done for me.

I am also grateful to the guys at the marina who accomodated me there letting me stay there for free for almost two weeks before I finally got a weather window to push off the island.

Happy Socks tied to a jet ski launching pad, the only mooring option that allowed me to climb (jump) aboard.

Finally pushing off Gran Canaria on the Boxing Day.

I made a good progress in the first couple of days going South with the following wind. I woke up on the following morning being greeted by a large pod of dolphins. That was the only time throughout my whole trip that I enjoyed their company.

Facing the Atlantic: Challenges at Sea

The following two weeks were difficult - I was being pushed up North by the Southerly winds while trying to row West. That put a lot of pressure on the steering lines as the rudder had to be kept turned to the port in order to keep the bearing. The lines, which were not new and a bit tired to start with began snapping. I also tore my left triceps as I was mostly using my left arm to row the boat.

I had some spare rope and kept repairing the steering set-up eventually reducing it to quite a basic system with the portside line going through a bite block and the starboard one tied around a cleat. In order to do the repairs I had to come out through the rear hatch, which was a bit risky in rough seas. I had to accept a risk of my cabin being hit by a rogue wave and getting flooded. I would put on my foul weather gear and try to act as a human cork to seal the hatch door while being hit by large waves and trying to be as quick as I could. At some point I used cable ties to re-attach the rudder as the quickest option. They did last for a couple of days and then the seas got calmer, which allowed me more time to find a more definitive solution.

Coming out of the hatch door to repair the rudder was not without a risk.

…and some temporary repairs with cable ties.

Problems with my steering continued and at some point I ran out of spare rope and blocks. Although I achieved a reasonable, albeit very basic result I was very concerned that it was not going to last that being week number three of my crossing. I had not even reached the Tropic of Cancer where the Trade Winds start blowing and I was concerned that my steering was going to give up again with no spares to repair it and two more months to go. I was using my Anaesthetic mindset - if there is a problem when the patient is asleep, but the surgery has not yet started, the safest thing to do is to wake the patient up! I do remember being absolutely sure that that was the right thing to do. I called my mentor Dave and told him that I wanted to get off.

Moments of Solitude and Reflection

“Is your life in danger? Is the boat sinking?”, were his immediate probing questions. “Well, if the answer is “no”, then it is not an emergency and you would have to pay (tens of thousands of £££) to a shipping company for a diversion of their ship. Plus, you will have to go wherever the ship is going, which might take a few weeks”, he continued. I had to sit down and look at my situation from a different angle, a position of an outsider, and not an insider. I was indeed safe and had achieved a reasonable result with my repairs - the steering was working and the boat was going in the right direction. I had to adopt a new mindset - patch things up and keep going at all costs! There are no perfect solutions out there in the middle of the Ocean, only acceptable ones that would last until conditions get better.

A week later I had another episode that nearly ended it for me. My hatch door started leaking during a storm with the cabin quickly filling up with water. It happened in the middle of the night in very rough seas and was quite scary. I temporarily sealed the hatch with some towels and called Dave telling him that it was likely the end of the road for me - had the boat capsized with water filling up the cabin it would have likely sunk with me inside it. “Is the water up to your ankles?”, he asked me calmly. “No”, was my reply. “Well, it is normal then! You have got it under control for now. Go to sleep, have some rest and we will come up with a solution tomorrow”. I did go to sleep and I did come up with a solution on the following day, using a duck tape and slices of rubber that I cut from a knee pad to seal the hatch. Those two episodes gave me confidence in my abilities to “find cracks in the wall”, to remain calm, identify and deal with problems that I had a control over. Also, I learned exactly what Dave was going to tell me if I had called him to ask for "an evacuation” if there was no immediate danger to me, or the boat. From then on, I never did.

There was another problem that was keeping me awake at night when I was rowing close to shipping lanes near the Continent - I was invisible to bigger ships. Because my AIS radar antenna was too short, tankers and cargo ships were not picking up the signal. I had to light up my flares a few times so that they could identify my position. Once, a big tanker was too close to me and the crew were no able to see the flares due to their line of sight. The captain asked me to read my GPS coordinates when we talked on the VHF radio. It was then that I found out that I was no table to see the numbers due to double vision caused by anti-sickness patches (Scopaderm) that I had stuck behind my ear earlier. They were very effective in dealing with sickness, but caused quite a severe double vision that prevented me from being able to read small text at close range. I told the captain to turn 15 degrees to the port and avoided an inevitable collision. There were other close encounters with tankers, but they all managed to see my flares. By the time, I left the shipping lines I had no flares left!

One of the ferry that I did not have to call as it was clearly not going to run me over!

There were beautiful sunrises and sunsets, which were leaving me speechless. Sometimes, I felt my eyes welling up because of the perfection, the beauty of my surroundings and the sheer privilege of being a small part of it, to be able to experience it all in such an intimate and unique way. The pictures do not do it justice.

As I was struggling through the unfavourable conditions during the day, I had to deploy a para-anchor overnight in order to fix my position and not being blown up North when sleeping. It was a tedious job, which involved tying knots, attaching shackles and feeding the main line (100 metres), retrieval line (120 metres) and the parachute itself in the right order, then retrieving it in the reverse order on the following morning. Both deployment and retrieval took around an hour each and were exhausting, especially at the end of a 12-hour rowing shift in rough seas.

Deploying the para-anchor - the parachute, the main line and the retrieval line are clearly visible.

One day I was too tired to bother with the para-anchor and decided to sleep it off without it. Below is the loop that shows my 24-hour “progress” - first drifting up North overnight, and then frantically trying to row back South on the following day arriving at the same place where I had started drifting from on the previous evening.

Despite the unfavourable conditions of my first month at sea, I managed to advance albeit very slowly down South towards the Tropic of Cancer. This is how the calmest day of my whole crossing looked like before I went through a weather front and was picked up by strong Northerly Trades:

As I was entering the Trade Wind territory, the skies became more ominous, the clouds darker bringing in squalls. Mornings often looked other-worldly like in the video below:

I learned what mid-Atlantic squalls really felt like. This was one of many, and I did learn to row through them later!

…like this one later on some time in February.

The most difficult, but the most important decision of the day, every day was to open up that bloody hatch, regardless of what was going on outside and inside! At the beginning of my crossing, I would just sit there frozen and unable to do it being overwhelmed, and sometimes scared by all the things that were waiting for me outside, things that have never materialised.it was sometimes quite unpleasant, but once out there on the deck, you just deal with what is actually happening, not what could potentially happen inside your head.

Opening up that bloody hatch is the most important decision of the day! If you give in to thinking about all the failures that you could experience on that day, week, month, the rest of your life, you would never live terrified of something that never happens.

That is a view of my cabin - a very small antrum where I basically had my meals, spoke on the phone as the internal antenna for my sat phone was only one meter long, etc; and a bed. Everything had to be secured when a particularly bad squall was coming in. There were storage compartments under the mattress where I kept my snacks, which went bad when the cabin was flooded during a storm. Everything went damp and mouldy after that for the whole duration of my crossing. I was not able to dry stuff on deck due to rough seas. It was only when I reached the Caribbean that things started drying out. That cabin turned into an oven overnight, an overheated plastic dog carrier with sealed off hatches and very little ventilation.

The everyday reality of ocean rowing is an extreme physical discomfort. There is no escape, you just have to come up with ways of somehow tolerating it. Not only that - you have to be able to get some rest and recovery before getting on the oars on the following day. You look forward to a breath of fresh air and an open space when inside the cabin, and a break from rowing, not sitting on your sore and ulcerated bottom, eating some better food and talking to your family when out on the deck. You simply cannot dwell on the pain of the moment, but rather try looking forward to some simple pleasures in the near future.

One of my biggest problems throughout my crossing were barnacles that were creating a strong drag as well as making steering difficult. In an ideal world, one is supposed to scrape them off every two, or three weeks.

Due to particularly strong Trades this year I was only able to clean the hull after two months at sea. The difference in speed and ease of steering afterwards were striking!

I continued to battle through very rough seas, rowing through frequent squalls and tropical storms, as well as dealing with scorching temperatures.

At about 300 miles from Barbados, I had to spend 6 days on para-anchor due to a tropical low pressure weather system messing up the Trades and sucking me up North. Here is a little video explaining my survival techniques that helped me get through a scorching heat in a liquid desert.

My last three weeks at sea were pretty dark - I had to go hard South in predominately easterly Trades and row almost parallel to the crests of waves, which was physically very demanding. I also ran out of snacks as most of them had gone bad when my cabin had got flooded earlier. I felt weak and was wasting away, and I was hallucinating badly. What kept me going was the realisation that I was doing my best every day. I was putting up 14-hour shifts at the oars without a single day off. My happiest moment of the day was the moment that I took my life jacket off knowing that I had given it my all that day. I was looking forward to that moment every day and I will never forget the feeling!

The last few days of my crossing consisted of ups and downs - I was constantly being pushed in the wrong direction by the local currents. On my final approach to Barbados, after having been pushed too much to the South and actually starting to fear that I might miss it, I finally caught a favourable current pushing me up North and rode it for a whole day making a good progress.

Going to bed that night, I saw the lights on the horizon and my drifting COG (course over ground - the true direction that the boat was drifting) was about 300 degrees, which was approximately the bearings I’d been rowing at during the day.

I woke up at about 1 a.m. and checked my COG, which to my dismay was 250 degrees then - too westerly, but I had not gone too far in that direction yet, so I convinced myself that it was just a temporary glitch and went back to bed. I then woke up at 5 only to discover that it had not been a glitch, and I had drifted South for about 8 miles, getting now quite close to the southern tip of the island.

Theoretically, it is possible to round the island from both the southern and northern sides, but the North is more favourable as the marina I was heading towards was in the North, and also the main port (and an American naval base) are in the South, which makes navigation in a small rowing boat just that much difficult.

I called my weather router Simon Rowell, and asked him for his opinion. He was already up and monitoring my progress. His exact words were - “Just try to row in either direction and see what works best”. Translation - “ you are the Captain, it is you big moment now”.

The wind was NE, about 20 kts and taking me directly towards the island. Whatever bearing I had chosen (N, or S) would have meant rowing at an angle to the wind-driven waves. The choice was basically between which side I’d have preferred to get hit at - port, or starboard.

So, I tried both and rowing up North actually felt easier. You have to understand that it was about 6 a.m. UTC (2 a.m. local time and totally dark, so I had to rely heavily on how it “felt”. As I rowed on, I was pleasantly surprised - I was actually beginning to progress rather quickly, going up North and gaining the miles lost over night rather quickly. The current was turning North again and I was riding it! It appeared that I’d made the right choice!

After a few hours of what I was now fairly certain was home run, I started noticing that my latitude plateaued and in fact, started going down again. I was being pushed South again, but what was more worrying, my drift to the West as just as strong. In fact, it was even stronger due to quite violent and persistent squalls. The island was getting bigger, its Eastern rocky shore more and more visible.

A quick call to the team and the decision was made to give it another hour of hard rowing N, almost parallel to the waves. The Northern tip of the island was about 6 miles away now, with the Eastern shore only about 8 miles from me.

One hour passed and jt became very clear that I was being pushed to the rocky Eastern shores too quickly. There is nowhere to land safely there and the decision had to be made there and then.

We were all in agreement that I needed a tow. Barbados Coastguard was contacted, and a couple of hours later I was towed not only around the Northern tip of the island, but into the marina itself, for which I’m very grateful.

Thus, my last 10 miles or so were not rowed by me. I accept this, and am very appreciative for the rescue of myself and the boat. I have done this crossing with my own personal goals in mind, which I have fully achieved. I will sleep well knowing that I had fought till the very end giving it everything I got left in the tank, and then some. The Ocean simply does not care, but I am grateful for the opportunity to pick up a good fight. I am still standing after it is finished.

Arrival in Barbados: Completing the 96-Day Journey

And this is my favourite video - the finish line of my 96-day ocean crossing. Battered and bruised, but not defeated!

Acknowledgments and Gratitude

The face of a happy woman. Thank you darling, for keeping all the day-to-day shit together while I was chasing my crazy dream. Thanks for believing me and in me, I am fully back now. I have not left anything important out there in the Ocean, just some stuff that needed to be buried somewhere long time ago, but I had never been able to find a ditch deep enough for it. 15.000 feet seemed deep enough so I have thrown it all away down into it..

I have made it, we have made it - thank you for living through it with me.

Love you.

Lessons Learned from the Atlantic Crossing

Looking back at my crossing now, I can say that my goals have been achieved. I overcame my inner demons of despair, self-pity and self-doubt and kept on moving forward, not forgetting to enjoy every stroke of it, however hard and impossible it felt at times. I have managed to raise a significant amount of money for my Ukraine medical charity and will make sure that it will be spent on a long-term project with the best possible outcome. More importantly, I feel (and know for a fact!) that I have inspired my Ukrainian friends to continue their daily fight taking one day at a time and finding cracks in the wall. I hope they could see that they are not forgotten and there are people out there who truly care about them.

Glory to Ukraine!

The work of Ukrops Charity continues and you could still support us by clicking the “Donate” button below. The Leo’s Row is finished, but we are still moving forward!

Leo Krivskiy 💙💛